Unlimited Lives is dead. It never quite figured out what it wanted to be. On to the next thing, then.

Deleted Scenes: Let it Be

March 27, 2013Deleted Scenes is going to be a collecion of pieces I wrote for other outlets, things that for one reason or another didn’t get published. They could be full 2,000-word articles, they could be 50-word blurbs. If I write it, it doesn’t get posted, and I think it’s good enough to publish, this is where it’ll end up.

Over the last two weeks, the good people over at popblerd.com have been posting their list of the best albums of the ’70s. It’s an interesting and fairly eclectic list, with most of the albums you’d expect and a few you might not; it’s worth checking out, even if music from the time before you were born isn’t your thing.

Over the last two weeks, the good people over at popblerd.com have been posting their list of the best albums of the ’70s. It’s an interesting and fairly eclectic list, with most of the albums you’d expect and a few you might not; it’s worth checking out, even if music from the time before you were born isn’t your thing.

I wrote a few blurbs for the list, including one for Bowie’s Aladdin Sane and one for Zeppelin’s III. I also wrote one for an album that ended up in the top 10: The Beatles’ Let it Be, one of my favorite Beatles albums, not to mention the only chance for a proper Beatles album to be listed in a list of “albums of the ’70s”. My blurb wasn’t the one to get published, so here they are: a couple of thoughts on The Beatles’ final album:

* * *

The Beatles – Let it Be (1970)

It’s no surprise, I’m sure, to see The Beatles show up on any list that they happen to be eligible for, and Let it Be was late for the ’60s by about five months, so here it is. Rarely does Let it Be make any noise as one of the best Beatles albums, because as Beatles albums go, it is uneven and unambitious. It was recorded before Abbey Road, but disagreements in its production style and the songs that were to be included kept it off of shelves until two years after it was recorded. Even as recently as ten years ago, a new version of the album was released — Let it Be…Naked — that purported to be closer to the “original version” of Let it Be.

Nobody ever follows the advice of the album’s title. Everyone seems to wish that it could be more, that it could be better than it is, largely thanks to the pedestal that everyone puts The Beatles on. Every album must be perfect, it must define its era, and if it doesn’t, the problem must be circumstance rather than the music itself.

The constant tinkering is unfortunate, because taken as it is, Let it Be is still a great album. “Across the Universe” and “Let it Be” are two of the band’s most identifiable musical statements, and for good reason; they are immediately catchy and beautifully layered pieces of music. “Get Back” is one of the best “rock ‘n roll Paul” songs The Beatles ever did, and George Harrison’s aggressively cynical “I Me Mine” is a display of his simplistic songwriting style at its best.

Sure, there are a couple of bombs on Let it Be; “Two of Us” is a pleasant throwback at best — a lousy way to open the album — and “The Long and Winding Road” is a dense, saccharine mess no matter which version you’re listening to. Still, the bright lights outshine the missteps, and while Let it Be may never be more than the sum of its parts, some of those parts are sufficiently brilliant to stand on their own.

Tools and Toys: Origin of a Gamer (#BoRT)

November 7, 2012Prologue: I promise I’m going to write some blog posts that aren’t #BoRT entries someday. I’m moving across states this week, nine months after last time I did it. Time is…well, it’s difficult to come by.

The theme of this month’s Blogs of the Round Table is “Origins”. Per #BoRT curator Alan Williamson: “What are your earliest memories of gaming? How do you think your childhood (or childish adulthood) experiences of gaming have influenced your life, if at all? Are there any game origin stories that reflect your own?”

Here goes nothing:

* * *

I didn’t “get” my first console. It was just, you know, there. I don’t even remember how I came to start playing it, just that I played it. I played Pong on it with a paddle, I played Combat on it with a joystick. It was an ugly thing, a giant brown box with conspicuous ports, buttons, and switches. It was my older brothers’ machine, and for some reason, when they moved out, they left it with my folks.

It was an Atari 2600. It didn’t change me or anything, I just can’t imagine my childhood without it.

It was an Atari 2600. It didn’t change me or anything, I just can’t imagine my childhood without it.

I remember playing Pac-Man on that machine. I loved Pac-Man on that machine. I’m fully aware, 30 years later, that the Atari 2600 port of Pac-Man is largely derided as perhaps the worst version of a classic game, but it didn’t matter. It’s amazing what can come off as brilliant when you don’t know that anything better exists. All I knew at that point was that it worked part of my brain that no other entertainment could. It also offered the first hints of my obsessive-compulsive tendencies when it came to video games; even when I was five years old, my Pac-Man strategy was to get all the dots first, saving all the power pellets for the end.

I remember playing Football on that machine. Honestly, I didn’t know what the hell was going on.

I remember playing E.T. on that machine. I may have played more E.T. than any other Atari game save for Pitfall II, certainly more than any other game that I “inherited” from my brothers. It was a fascinating and alien thing. It was aggressively strange, punishing, and difficult, and I wanted so badly to understand it. I got pretty good at it, if I’m being honest.

I remember playing Yars’ Revenge, Venture, and Super Breakout. I remember playing Pitfall, and Kaboom, and River Raid. I remember playing some odd Sesame Street thing that involved an exclusive number-pad peripheral thing. And I remember playing them over, and over, and over again. Somehow, my parents let me stick with these games, they let me treat them like any other toy, and not like the devil in the TV.

Heck, I should probably thank them for that.

The first machine I was alive for when it was introduced into the house was an IBM PCJr. As if to try and convince me that this machine was a necessary component of our household, my dad showed me Jumpman on the first day that computer was in the house.

Do you remember Jumpman? Think a sub-8-bit version of N+ and you’re probably not too far off.

My god. I just remembered that computer was in the kitchen. THE KITCHEN. Why was it in the kitchen?

As much as the 2600 showed me what video games could be and do, that PCJr showed me what they were made of. I bought books of BASIC programs that I one-fingered into files, LOADed, and RUNned. Every so often, a game I bought in the store would error out, and I’d get a glimpse of the source code, a stray GOSUB or a division by zero error. It was proof that these things were written, line by line, by actual honest to goodness humans. I admired these humans, even at six years old. I wanted to meet them, and I wanted to be them. I wanted to know what it was like to make something as open-ended and gleefully difficult as King’s Quest (a PCJr exclusive when it was first released!) and as utterly mysterious and far-reaching as In Search of the Most Amazing Thing.

Where the 2600 represented the future of toys, the PCJr represented endless possibility, a world in which creation and consumption could coexist and intermingle, a world in which I could, when I learned enough, change my games to suit my needs and interests.

Could I have articulated all that then? Hell no. Still, I think it was there in an abstract sense. Just as a child can sense tension even when all the grownups in the room are still plastering smiles on their faces, a child also knows when the future is knocking on the door.

My brothers, and then my father, brought the future into our house. I didn’t even have to ask. It’s no wonder I can’t just “play” games. I have to understand them, too.

The Limits of “Fun” (#BoRT)

September 3, 2012 Oh hey, Alan Williamson over at Critical Distance is bringing back Blogs of the Round Table! I used to have some fun bouncing from blog to blog reading these things, so I think I’ll give this one a shot. Here’s this month’s assignment:

Oh hey, Alan Williamson over at Critical Distance is bringing back Blogs of the Round Table! I used to have some fun bouncing from blog to blog reading these things, so I think I’ll give this one a shot. Here’s this month’s assignment:

2K’s Chris Hartmann recently said that achieving photorealism was the key to opening ‘new genres’ of games. Without discussing whether or not this is true (it isn’t), what genres or subjects have games left uncovered, and what should they be focusing on? Alternatively, if photorealism isn’t the limiting factor on the diversification and evolution of gaming experiences, what is? Were Belgian Eurodance group 2 Unlimited right with their assertion that, in fact, there are No Limits?

Ah…hm. Right. Since I have never felt inspired by a discussion of genre, I’ll go with option 2, thank you.

* * *

You know, it’s a funny thing, looking back at where games have came from, because for almost any individual trying to look back, it becomes a personal history. “Where have games come from” could have as much to do with Colecovision, Turbografx-16, and Virtual Boy (well, maybe not Virtual Boy) as they do Atari 2600, Nintendo Entertainment System, and Sega Genesis. One person’s treasure is another’s unknown quantity, and there have been enough games and gaming systems out in the last 35 or so years as for it to be a virtual impossibility that anyone could do a comprehensive history based on personal experience.

As such, we have to share our experience. The internet is the obvious vehicle for that now, as blogs, user reviews, and actual legitimate criticism are available in abundance for those willing to look. For a while, though, we didn’t have such obvious venues for discussion.

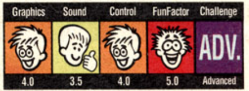

We had magazines, magazines that offered reviews with rating scales that looked like this:

Don’t get me wrong, I loved GamePro, and probably read more issues multiple times than was healthy for a growing boy in the mid-’90s. It was one of the most identifiable gaming mags out there, and it was a common enough touchpoint to be something you could talk about with friends in school hallways. It was so common, in fact, that its reviews felt a bit like gospel truth at the time. These reviews were rated in the four categories that you can see above: Graphics, Sounds, Control, and something GamePro called “FunFactor”. It was this last category that was typically seen as the most important; after all, one could get past primitive visuals, lousy music, and even shaky controls if the game was fun to play. That was the point of games, after all, right? Fun?

It is the idea of “games” and “fun” being necessarily paired that limits the medium. When we fall into the trap of comparing games to books or movies and marveling at just how little the narrative structures of games have in common with those of other mediums, much of the difference can be attributed to the desire of the developer to give the player something “fun” to play. The words “player” and “play” themselves carry with them connotations of fun, unlike, say, “reader” or “viewer”. Books and films are offered the opportunity to be Serious Business by not necessitating that the consumer of such media have a pleasurable experience. One can marvel at the performance of Daniel Day-Lewis in There Will Be Blood while never ever suffering from the delusion that it is a “fun” movie. One can absorb something as nihilistic as The Road without cracking a single smile. These are great works, but they are allowed to be so by not being bound to the constraint of offering enjoyment to their audiences. Some art is work.

Knowing that there are films, or books, or even pieces of music (hey, Lou Reed) that are specifically geared toward making their audiences work toward understanding enhances these mediums as a whole. The idea that we should be “playing” games, presumably having “fun” while we do so, necessarily reduces the possibilities of the medium.

There are counterexamples, of course, mostly at the fringes of PC gaming, but there are a few major publishers who have been willing to take the risk of offering an experience to gamers that is not at all intended to be fun. Perhaps the recent highest profile of these counterexamples is Spec Ops: The Line, a game whose gleeful toying with player expectations is expertly detailed here. Sure, some of it falls into shooter conventions, but its questioning of the genre and of the player for enjoying that genre is a commendable step toward challenging consumers of these games, rather than simply pandering to their base desires. Games like No More Heroes and the Fable series monetize manual labor, repetitive tasks that aren’t really fun, but do benefit the player in a very real way. And then, of course, there are little things like Passage, which is more like an interactive short story, except without the words that typically get in the way of such things.

There are counterexamples, of course, mostly at the fringes of PC gaming, but there are a few major publishers who have been willing to take the risk of offering an experience to gamers that is not at all intended to be fun. Perhaps the recent highest profile of these counterexamples is Spec Ops: The Line, a game whose gleeful toying with player expectations is expertly detailed here. Sure, some of it falls into shooter conventions, but its questioning of the genre and of the player for enjoying that genre is a commendable step toward challenging consumers of these games, rather than simply pandering to their base desires. Games like No More Heroes and the Fable series monetize manual labor, repetitive tasks that aren’t really fun, but do benefit the player in a very real way. And then, of course, there are little things like Passage, which is more like an interactive short story, except without the words that typically get in the way of such things.

Believe me, I realize that the idea that a game doesn’t have to be “fun” to be great isn’t a new concept, but such an idea is certainly one of the limitations of the medium. The money is in fun; people don’t play Call of Duty or Gears of War or even World of Warcraft to be intellectually challenged. People play those games because they satisfy some definition of “fun”. At some point, our money should start going toward things that aren’t “fun”. Our money should start speaking to experiences that offer a range of emotional responses, that draw us into experience that make us question our values, our preconceptions, and our biases.

Maybe instead of looking for the Citizen Kane of gaming, we should be looking for, say, its Taxi Driver.

Endgame: The Legend of Zelda, Second Quest

May 23, 2012 As it turned out, I couldn’t do it.

As it turned out, I couldn’t do it.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. I actually set out to do the one thing I hadn’t tried in the overworld: I went through each screen — every single one — one by one, and bombed, burned, pushed, and whistled my way through them. I found a small pile of secrets to everybody. I found many more grumpy old men who made me pay to fix their doors. I found a couple of shops, some old ladies selling potions, and a shocking number of money making games.

And yet, I never found the seventh dungeon.

As a fun fellow who calls himself Octopus Prime mentions in this thread, “It lies concealed under a completely innocuous shrub on a screen full of shrubs.” Even as I willed myself the patience of exiting and re-entering each highly forested room to try and burn down every god forsaken tree, I never found it. My suspicion is that I “missed” – that my attempts to burn multiple trees at once in order to reduce the time it took to go through every single one got slightly lazier than it was allowed to; that while I thought I had tried to burn that bush, I never actually did. Once I was done with that room — once I could assure myself that I had tried everything there was to try in that room — I never went back. There was no reason to, unless I wanted to try bombing trees.

Thankfully, I never did try bombing trees. While I did go ahead and force my way through dungeon 8 before I ever found dungeon 7 (something that goes against the pseudo-OCD behaviors I typically display while running through games like this), I never got desperate enough to think that maybe shooting arrows at rocks would help, or anything like that. This is where, long ago, the primitive sort of crowdsourcing was the only way to win; advice from a friend, or a couple of hours of play in the hands of my brother. I can confidently say I never would have found that dungeon, and I’d have put the game down having still (still!) never finished the second quest.

I’m glad even my stubbornness has its limits. If I had spent another 10 hours looking for that dungeon, eventually finding it, and then almost immediately finding the red candle that lives in it, I’d have had to seek a refund for my shattered 3DS on account of “a destructive sense of irony”.

That out of the way, and free to get back to the business of exploring things whose existence I had not yet come to doubt, it didn’t take all that long (comparatively) to finish out the rest of the game. Even finding the red ring and silver arrow didn’t feel like terrible awful trudges through the unknown. Other than a mildly insidious multi-room moving block puzzle in the final dungeon, it was pretty straightforward the rest of the way through. Awful blue wizzrobes here, awful red bubbles there, and a couple of awful triple dodongo rooms later, Ganon showed himself once again, and with no new tricks up his sleeve, he quickly fell to dust once again:

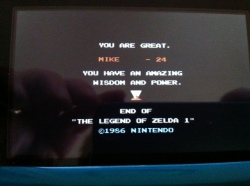

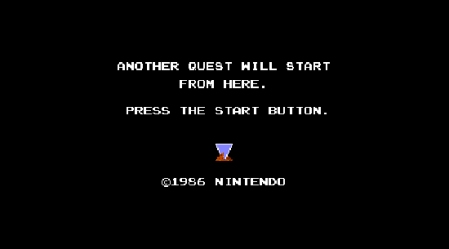

And then, The Legend of Zelda told me I was “great”, for lo, I had only (well, “only”) died 24 times over the course of two separate adventures:

And I thought, “you know what? I am great.” Then I powered down.

There’s a beautiful balance that The Legend of Zelda strikes, between setting a certain set of expectations and rules, and then slowly breaking them down. You see this a bit in the first adventure — figuring out that you can bomb your way into rooms unmarked on a dungeon map is one of the great little secrets that everyone who conquers the first adventure eventually has to come to realize, since finding these unmarked rooms is actually necessary in the final dungeon. The second adventure, however, is full of this — between walls you can walk through, advice whose meaning changes, and whistles that could blow open a staircase pretty much anywhere, the second quest is a tremendous mash of “everything you know is wrong”. There are even old men more ornery than the “door repair charge” guys, old men who demand either 50 coins or a heart container(!) before they allow you to proceed.

The beauty of it is that if you’ve put the time into conquering the first quest, none of the second quest will really feel impossible. It’ll throw you for a loop, sure, but the ways in which the rules break in the second quest are introduced just as gradually as those same rules were set in the first. Throw your assumptions about what you can and can’t do out the window a bit, and you find an open world that’s even more “open” than the first quest even suggests.

Maybe you won’t find everything, but it won’t be because the game cheated. It’ll only be for lack of diligence.

Even as it delayed my progress on other things, taking on the second quest was a pursuit worth doing. Best of all, I can finally claim the mastery of it that should accompany my other Legend of Zelda-related claim: namely, that it is the best game the NES ever saw.

Took long enough.

The Legend of Zelda. Second Quest. Search for the Seventh Dungeon. Day 8.

May 18, 2012 I don’t know how much longer I can hold out.

I don’t know how much longer I can hold out.

Until now, a random survey was enough. Explore the world I know, set some bombs in the conspicuous spots, explore the dungeons as thoroughly as I can muster, and try to burn every tree I find. And now, it’s suddenly not enough.

I almost gave up at the sixth dungeon. It almost had me. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine that I’d be blowing a whistle to make a gravestone disappear. I’d tried to move that same gravestone countless times before that, sure that I had simply not pushed for long enough, or perhaps that I had let my fingers slip and gave it a crooked push. It never budged. It was waiting for a melody.

The Legend of Zelda‘s second quest has that effect on you. Every time it breaks the rules that the first quest laid out, every time it opens up one more possible place to hide something, you don’t feel as though you’ve accomplished something by making that possibility a reality. Rather, there’s a despair with uncovering the secrets of the second quest. It’s the knowledge, once you blow the whistle and open up a random stairwell in the desert, that you’re going to have to blow the whistle in every single screen of the overworld if you want to uncover all its secrets.

Scratch that — it’s not just the secrets you need to uncover. It’s the dungeons. These are the necessary pieces of conquering the quest. And they could be anywhere.

It’s the terror of the unknown. It breaks you down. It makes GameFAQs look awfully enticing.

Part of my goal in returning to these old games was to inspire the nostalgia of playing games before the internet age. Playing games felt different in a time before spoilers were inevitable and answers were readily available. When you ran into a dead end and you had no idea how to progress, you typically had three options: crowdsource an answer from any friends who might also have been playing the game, spend some money to call a hotline or buy a strategy guide, or just run bull-headed back into the game convinced that this was it, this was the attempt when a solution was going to become clear.Really, it’s not that different from the paid-DLC model that instantly levels up your character. How much money could Nintendo have made if they had come up with a way to offer $4.99 paid “Dungeon-Finder” DLC? What if they offered the Master Sword as a bonus?

It certainly would have been awfully enticing in a time like this.

I mean, what kind of sadistic game encourages you to not only bomb every wall in every dungeon, but attempt to walk through it? The very first dungeon in the second quest makes it very clear that the map means nothing, so it doesn’t even matter if you think there’s a room there. You’d better try and get through that wall, or risk missing something very important.I thought I could hold out. I did. I thought I had the patience to look under every rock, to methodically search every room. I am operating under a few basic assumptions: there is a maximum of one visible or hidden door, combined, in every overworld panel. Every treasure necessary to uncover a higher-numbered dungeon can be found either in the overworld or in a lower-numbered dungeon.

Rafts need docks to be launched.

Even the master sword can’t break down a wall like a bomb can.

How do I know that any of these are even valid? In my searching, I’ve found the entrances to the eighth and ninth dungeons. How do I know that I won’t find the entrance to the seventh dungeon somewhere inside the eighth dungeon?

That’s the issue. I don’t know. And I don’t know how much longer I can keep up the search.